polympart: About 8 billion tons of plastic has been produced globally since the 1950s, but only 10% has actually been recycled.

Recycling is increasingly seen as an unsuitable solution to the growing volume of food waste produced by the world.

In addition to reducing our overall consumption levels, addressing the waste crisis will require more support for new forms of packaging such as those made from compostable materials.

In 1970, packaging manufacturer Container Corporation of America was on the hunt for a new symbol to help companies showcase a commitment to recycling. University of Southern California architecture major Gary Anderson spent just two days designing the entry that would come out on top of a field of 500. The winning three-arrow symbol was awarded $2,000 in prize money and was released into the public domain.

It is now used on products in every corner of the globe and is considered one of the most recognisable graphic symbols. In the years since, recycling has become the go-to solution to our waste woes, and Anderson’s mark is a universal indicator of corporate commitment to people and planet. As a result, consumers are comfortable using a larger amount of a resource when recycling is an option for its disposal.

The truth about recycling is much murkier, however. Just because a product features the symbol, it’s not certain that it will be recycled, especially in the case of plastic.

Problem Plastics

Approximately 8 billion tons of plastic have been produced since the 1950s and more than 300 million tons are now made each year. Although recycling has been mainstream for decades, and mechanical recycling works well for rigid plastics such as PET and mono materials, 10% of all plastic ever made has actually been recycled, at best.

There are many factors contributing to this figure. Some individuals and businesses still don’t make efforts to separate plastic from other waste. Whole nations export their plastic to be recycled without checking if that actually happens. Some plastic packaging – crisp packets for example – are multi-laminates, with other materials including paper or aluminium combined with the plastic meaning it cannot be processed in the recycling system. Other packaging such as flexibles are not economic to recycle. Plastic contaminated with food won’t be recycled either. Only clean plastic makes it through the system.

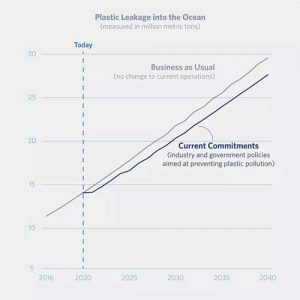

There are ongoing efforts to combat these issues. But the rate of our consumption of plastic – past and present – means recycling alone isn’t going to get us out of the waste crisis. Of the industry and government commitments made to-date, by 2040 the annual volume of plastic flowing into the ocean will be reduced by just 7%.

The rate of our consumption of plastic – past and present – means recycling alone isn’t going to get us out of the waste crisis.

The solutions

It will take a global effort to scale upstream and downstream solutions to combat plastic pollution. Better recycling will play a role, as will reuse and improved waste collection. But shifting the spotlight towards reducing the production of plastic is critical to each of these efforts. And a major contributor to reducing plastic production is replacing it with alternative, more sustainable materials.

Paper packaging can work – it biodegrades significantly quicker than plastic and is easily recycled. But trees grow too slowly to make this a truly sustainable option. They must be protected and their use limited. Paper also cannot offer the functionality of plastic required in our modern lives.

Food packaging is a case in point. We use plastic to preserve fresh produce because it acts as a barrier to the elements that increase the speed of decomposition. It’s the difficult-to-recycle plastic packaging that performs this purpose in most cases, which makes this a prime candidate for an alternative material.

Finding sustainable and functional alternatives is sticky territory

Materials sold as “biodegradable” are not required to adhere to any timeframe in which to break down, meaning some sit in landfill for years alongside conventional plastics. One study on biodegradable bags found they were still able to carry shopping after being buried for three years.

Oxo-degradable materials provide another potential solution. These conventional plastics have chemical additions that allow them to break down at a faster rate. They can leave behind microplastics, however, which accumulate in our oceans. When consumed by marine life, microplastics enter our food chain and ultimately our bodies. The European Commission banned oxo-degradable plastics in 2019 as a result.

For the compostable packaging industry to grow and continue to invest in research and development, it will require partners throughout the supply chain – brand owners, manufacturers, and governments – to be aligned on the solution.

Compostable packaging is an outlier as it has to be certified to be sold. Certification requires it to degrade into non-toxic particles within a specific timeframe, either in home composting bins or in industrial composters. Under these conditions it becomes compost that can be used to fertilise our depleting soils, leaving no waste behind.

For the compostable packaging industry to grow and continue to invest in research and development, it will require partners throughout the supply chain – brand owners, manufacturers, and governments – to be aligned on the solution.

plastics recycling has its limitations

When it comes to the difficult-to-recycle plastics, compostable packaging is a readily available solution. Where flexible plastic packaging was once necessary to protect shelf-life, compostable packaging now provides a better solution. A recent study found that microperforated compostable packaging extended the shelf-life of cucumbers by five days when compared to conventional plastic packaging. And if the food isn’t eaten before it goes bad, the packaging can be disposed of in food waste bins to be composted alongside it. R&D efforts mean compostable packaging’s applications are only growing, making them a viable solution to flexible plastic packaging, bags, pouches and more.

The recycling mark may be among the most recognisable symbols in use today, but we must be mindful that plastics recycling has its limitations. With the rate of plastic production only rising, there’s an urgent need for businesses and governments alike to champion other answers to the crisis. There is no silver bullet, but a combination of upstream and downstream solutions that include a shift away from plastic towards alternatives, including compostable packaging, will make a significant difference.

source: https://www.weforum.org